For the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, 1945–1964 was a time of high economic growth and general prosperity. It was also a time of confrontation as the capitalist United States and its allies politically opposed the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

and other

communist state

A communist state, also known as a Marxist–Leninist state, is a one-party state that is administered and governed by a communist party guided by Marxism–Leninism. Marxism–Leninism was the state ideology of the Soviet Union, the Comint ...

s; the

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

had begun.

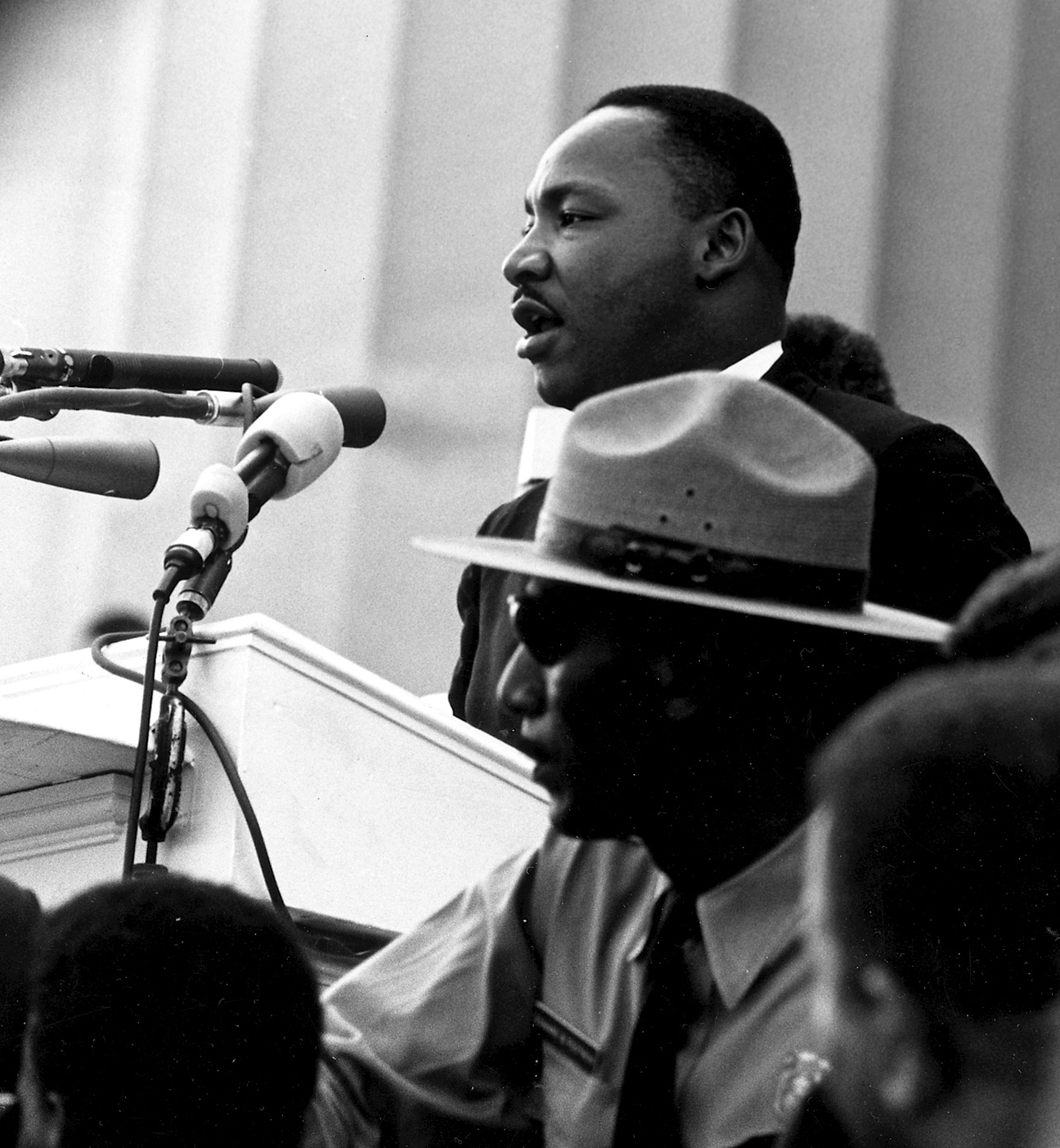

African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

united and organized, and a triumph of the

civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

ended

Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the Sout ...

segregation in the

Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

. Further laws were passed that made discrimination illegal and provided federal oversight to guarantee voting rights.

Early in the period, an active foreign policy was pursued to help Western Europe and Asia recover from the devastation of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. The

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

helped Western Europe rebuild from wartime devastation. The main American goal was to contain the expansion of

communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

, which was controlled by the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

until

China broke away about 1960. An arms race escalated through increasingly powerful nuclear weapons. The Soviets formed the

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact (WP) or Treaty of Warsaw, formally the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, was a collective defense treaty signed in Warsaw, Poland, between the Soviet Union and seven other Eastern Bloc socialist republic ...

of European satellites to oppose the American-led

North Atlantic Treaty Organization

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

(NATO) alliance. The U.S. fought a bloody, inconclusive war in

Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

and was escalating the war in

Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

as the period ended.

Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 200 ...

took power in Cuba, and when the USSR sent in nuclear missiles to defend it, the

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

of 1962 was triggered with the U.S., the most dangerous point of the era.

On the domestic front, after a short transition, the economy grew rapidly, with widespread prosperity, rising wages, and the movement of most of the remaining farmers to the towns and cities. Politically, the era was dominated by liberal Democrats who held together with the

New Deal Coalition:

Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

(1945–1953),

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

(1961–1963) and

Lyndon Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

(1963–1969). Republican

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

(1953–1961) was a moderate who did not attempt to reverse New Deal programs such as regulation of business and support for labor unions; he expanded Social Security and built the interstate highway system. For most of the period, the Democrats controlled Congress; however, they were usually unable to pass as much liberal legislation as they had hoped because of the power of the

Conservative Coalition. The

Liberal coalition

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sex-positive feminism, Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Art ...

took control of Congress after Kennedy's assassination in 1963, and launched the

Great Society

The Great Society was a set of domestic programs in the United States launched by Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964–65. The term was first coined during a 1964 commencement address by President Lyndon B. Johnson at the University ...

.

This period witnessed the rise of suburbs and a growing middle class.

Communitarianism

Communitarianism is a philosophy that emphasizes the connection between the individual and the community. Its overriding philosophy is based upon the belief that a person's social identity and personality are largely molded by community relati ...

and measurable

social capital

Social capital is "the networks of relationships among people who live and work in a particular society, enabling that society to function effectively". It involves the effective functioning of social groups through interpersonal relationships ...

was at its highest point during this time.

Cold War

The Cold War (1945–1991) was the continuing state of political conflict, military tension, and economic competition between the Soviet Union and its

satellite state

A satellite state or dependent state is a country that is formally independent in the world, but under heavy political, economic, and military influence or control from another country. The term was coined by analogy to planetary objects orbiting ...

s, and the powers of the Western world, led by the United States. Although the primary participants' military forces never officially clashed directly, they expressed the conflict through military coalitions, strategic conventional force deployments, a

nuclear arms race

The nuclear arms race was an arms race competition for supremacy in nuclear warfare between the United States, the Soviet Union, and their respective allies during the Cold War. During this same period, in addition to the American and Soviet nuc ...

, espionage,

proxy wars

A proxy war is an armed conflict between two states or non-state actors, one or both of which act at the instigation or on behalf of other parties that are not directly involved in the hostilities. In order for a conflict to be considered a pr ...

, propaganda, and technological competition, e.g., the

Space Race

The Space Race was a 20th-century competition between two Cold War rivals, the United States and the Soviet Union, to achieve superior spaceflight capability. It had its origins in the ballistic missile-based nuclear arms race between the tw ...

.

Origins

While Roosevelt was confident he could deal with Stalin after the war, Truman was much more suspicious. The United States provided large-scale grants to Western Europe under the

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program, ERP) was an American initiative enacted in 1948 to provide foreign aid to Western Europe. The United States transferred over $13 billion (equivalent of about $ in ) in economic re ...

(1948–1951), leading to a rapid economic recovery. The Soviet Union refused to allow its satellites to receive American aid. Instead, the Kremlin used local communist parties, and the

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

, to control Eastern Europe in totalitarian fashion. Britain, in deep financial trouble, could no longer support Greece in its civil war with the communists. They asked the United States to take over their role in Greece. With bipartisan support in Congress, Truman responded with the

Truman Doctrine

The Truman Doctrine is an American foreign policy that pledged American "support for democracies against authoritarian threats." The doctrine originated with the primary goal of containing Soviet geopolitical expansion during the Cold War. It was ...

in 1947. Truman followed the intellectual leadership of the State Department, which, especially under the guidance of

George F. Kennan

George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 – March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He was best known as an advocate of a policy of containment of Soviet expansion during the Cold War. He lectured widely and wrote scholarly hist ...

, called for

containment

Containment was a geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''cordon sanitaire'', which was ...

of Soviet communist expansion. The idea was that internal contradictions, such as diverse nationalism, would ultimately undermine Soviet ambitions.

By 1947, the Soviets had fully absorbed the three Baltic nations, and effectively controlled Poland, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Bulgaria. Austria and Finland were neutral and demilitarized. The Kremlin did not control Yugoslavia, which had a separate communist regime under

Marshall Tito

Josip Broz ( sh-Cyrl, Јосип Броз, ; 7 May 1892 – 4 May 1980), commonly known as Tito (; sh-Cyrl, Тито, links=no, ), was a Yugoslav communist revolutionary and statesman, serving in various positions from 1943 until his death ...

; They had a permanent bitter break in 1948. The Cold War lines stabilized in Europe along the

Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. The term symbolizes the efforts by the Soviet Union (USSR) to block itself and its s ...

, and there was no fighting. The United States helped form a strong military alliance in

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

in 1949 including most of the nations of Western Europe, and Canada. In Asia, however, there was much more movement. The United States failed to negotiate a settlement between its ally, nationalist China under

Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

, and the communists under

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC) ...

. The communists took over

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

in 1949 and the nationalist government moved to the offshore island of Formosa (Taiwan), which came under American protection. Local communist movements attempted to take over all of Korea (1950) and Vietnam (1954). Communist hegemony covered one third of the world's land while the United States emerged as the world's more influential superpower, and formed a worldwide network of military alliances.

There were fundamental contrasts between the visions of the United States and the Soviet Union, between capitalist democracy and totalitarian communism. The United States envisioned the new

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

as a

Wilsonian

Wilsonianism, or Wilsonian idealism, is a certain type of foreign policy advice. The term comes from the ideas and proposals of President Woodrow Wilson. He issued his famous Fourteen Points in January 1918 as a basis for ending World War I and p ...

tool to resolve future troubles, but it failed in that purpose. The U.S. rejected totalitarianism and colonialism, in line with the principles laid down by the

Atlantic Charter

The Atlantic Charter was a statement issued on 14 August 1941 that set out American and British goals for the world after the end of World War II. The joint statement, later dubbed the Atlantic Charter, outlined the aims of the United States and ...

of 1941: self-determination, equal economic access, and a rebuilt capitalist, democratic Europe that could again serve as a hub in world affairs.

Containment

For NATO, containment of the expansion of Soviet influence became foreign policy doctrine; the expectation was that eventually the inefficient Soviet system would collapse of internal weakness, and no "hot" war (that is, one with large-scale combat) would be necessary. Containment was supported by Republicans (led by Senator

Arthur Vandenberg

Arthur Hendrick Vandenberg Sr. (March 22, 1884April 18, 1951) was an American politician who served as a United States senator from Michigan from 1928 to 1951. A member of the Republican Party, he participated in the creation of the United Nati ...

of Michigan, Governor

Thomas Dewey

Thomas Edmund Dewey (March 24, 1902 – March 16, 1971) was an American lawyer, prosecutor, and politician who served as the 47th governor of New York from 1943 to 1954. He was the Republican candidate for president in 1944 and 1948: although ...

of New York, and general

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

), but was opposed by the isolationists led by Senator

Robert A. Taft

Robert Alphonso Taft Sr. (September 8, 1889 – July 31, 1953) was an American politician, lawyer, and scion of the Republican Party's Taft family. Taft represented Ohio in the United States Senate, briefly served as Senate Majority Leade ...

of Ohio.

1949–1953

In 1949, the communist leader

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC) ...

won control of mainland China in a civil war, established the

People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, then traveled to Moscow where he negotiated the

. China had thus moved from a close ally of the U.S. to a bitter enemy, and the two fought each other starting in late 1950 in Korea. The Truman administration responded with a secret 1950 plan,

NSC 68 United States Objectives and Programs for National Security, better known as NSC68, was a 66-page top secret National Security Council (NSC) policy paper drafted by the Department of State and Department of Defense and presented to President Harry ...

, designed to confront the communists with large-scale defense spending. The Russians had built an atomic bomb by 1949, much sooner than expected. Truman then ordered the development of the

hydrogen bomb

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

.

Two of the spies who gave atomic secrets to Russia were tried and executed.

France was hard-pressed by communist insurgents in the

First Indochina War

The First Indochina War (generally known as the Indochina War in France, and as the Anti-French Resistance War in Vietnam) began in French Indochina from 19 December 1946 to 20 July 1954 between France and Việt Minh (Democratic Republic of Vi ...

. The U.S. in 1950 started to fund the French effort on the proviso that the Vietnamese be given more autonomy.

Korean War

Stalin approved a

North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu River, Y ...

n plan to invade U.S.-supported

South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and sharing a Korean Demilitarized Zone, land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed ...

in June 1950. President Truman immediately and unexpectedly implemented the containment policy by a full-scale commitment of American and UN forces to Korea. He did not consult or gain approval of Congress but did gain the approval of the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

(UN) to drive back the North Koreans and re-unite that country in terms of a

rollback

In political science, rollback is the strategy of forcing a change in the major policies of a state, usually by replacing its ruling regime. It contrasts with containment, which means preventing the expansion of that state; and with détente, w ...

strategy. While originally a civil war, it quickly escalated into a

proxy war

A proxy war is an armed conflict between two states or non-state actors, one or both of which act at the instigation or on behalf of other parties that are not directly involved in the hostilities. In order for a conflict to be considered a pr ...

between the United States and its allies and the communist powers of the People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union.

After a few weeks of retreat, on September 15 General

Douglas MacArthur

Douglas MacArthur (26 January 18805 April 1964) was an American military leader who served as General of the Army for the United States, as well as a field marshal to the Philippine Army. He had served with distinction in World War I, was C ...

conducted

an amphibious landing at the city of

Inchon

Incheon (; ; or Inch'ŏn; literally "kind river"), formerly Jemulpo or Chemulp'o (제물포) until the period after 1910, officially the Incheon Metropolitan City (인천광역시, 仁川廣域市), is a city located in northwestern South Kore ...

(Song Do port). The North Korean army collapsed, and within a few days, MacArthur's army retook

Seoul

Seoul (; ; ), officially known as the Seoul Special City, is the capital and largest metropolis of South Korea.Before 1972, Seoul was the ''de jure'' capital of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea) as stated iArticle 103 ...

(South Korea's capital). He then pushed north,

capturing Pyongyang in October. This advantage was lost when hundreds of thousands of Chinese entered an undeclared war against the United States and pushed the US/UN/Korean forces back to the original starting line, the 38th parallel.

MacArthur planned for a full-scale invasion of China, but this was against the wishes of President

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

and others who wanted a limited war. He was dismissed and replaced by General

Matthew Ridgeway.

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

in 1952 campaigned against Truman's failures of "Korea, Communism and Corruption," promising to go to Korea himself and end the war. By threatening to use nuclear weapons in 1953, Eisenhower ended the war with a truce that is still in effect.

An

armistice agreement was finally agreed to by the

United Nations Command

United Nations Command (UNC or UN Command) is the multinational military force established to support the South Korea, Republic of Korea (South Korea) during and after the Korean War. It was the first international unified command in history, an ...

, the

Korean People's Army

The Korean People's Army (KPA; ) is the military force of North Korea and the armed wing of the Workers' Party of Korea (WPK). Under the ''Songun'' policy, it is the central institution of North Korean society. Currently, WPK General Sec ...

, and the

Chinese People's Volunteer Army

The People's Volunteer Army (PVA) was the armed expeditionary forces deployed by the People's Republic of China during the Korean War. Although all units in the PVA were actually transferred from the People's Liberation Army under the order ...

on July 27, 1953. The war left 33,742 American soldiers dead, 92,134 wounded, and 80,000

missing in action

Missing in action (MIA) is a casualty classification assigned to combatants, military chaplains, combat medics, and prisoners of war who are reported missing during wartime or ceasefire. They may have been killed, wounded, captured, ex ...

(MIA) or

prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of wa ...

(POW). Estimates place

Korean and Chinese casualties at 1,000,000–1,400,000 dead or wounded, and 140,000 MIA or POW.

[ According to Chalmers Johnson, the death toll is 14,000–30,000]

Anti-communism and McCarthyism: 1947–1954

In 1947, well before McCarthy became active, the

Conservative Coalition in Congress passed the

Taft Hartley Act, designed to balance the rights of management and unions, and delegitimizing communist union leaders. The challenge of rooting out communists from labor unions and the Democratic Party was successfully undertaken by liberals, such as

Walter Reuther

Walter Philip Reuther (; September 1, 1907 – May 9, 1970) was an American leader of Labor unions in the United States, organized labor and Civil rights movements, civil rights activist who built the United Automobile Workers (UAW) into one of ...

of the autoworkers union and

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

of the Screen Actors Guild (Reagan was a liberal Democrat at the time). Many of the purged leftists joined the presidential campaign in 1948 of FDR's Vice President

Henry A. Wallace.

The

House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloy ...

, with young Congressman

Richard M. Nixon playing a central role, accused

Alger Hiss

Alger Hiss (November 11, 1904 – November 15, 1996) was an American government official accused in 1948 of having spied for the Soviet Union in the 1930s. Statutes of limitations had expired for espionage, but he was convicted of perjury in con ...

, a top Roosevelt aide, of being a communist spy, using testimony and documents provided by

Whittaker Chambers

Whittaker Chambers (born Jay Vivian Chambers; April 1, 1901 – July 9, 1961) was an American writer-editor, who, after early years as a Communist Party member (1925) and Soviet spy (1932–1938), defected from the Soviet underground (1938), ...

. Hiss was convicted and sent to prison, with the anti-communists gaining a powerful political weapon. It launched Nixon's meteoric rise to the Senate (1950) and the vice presidency (1952).

With anxiety over communism in Korea and China reaching fever pitch in 1950, a previously obscure Senator,

Joe McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death in 1957. Beginning in 1950, McCarthy became the most vis ...

of Wisconsin, launched Congressional investigations into the cover-up of spies in the government. McCarthy dominated the media, and used reckless allegations and tactics that allowed his opponents to effectively counterattack. Irish Catholics (including conservative wunderkind

William F. Buckley, Jr.

William Frank Buckley Jr. (born William Francis Buckley; November 24, 1925 – February 27, 2008) was an American public intellectual, conservative author and political commentator. In 1955, he founded ''National Review'', the magazine that stim ...

and the

Kennedy Family

The Kennedy family is an American political family that has long been prominent in American politics, public service, entertainment, and business. In 1884, 35 years after the family's arrival from Ireland, Patrick Joseph "P. J." Kennedy be ...

) were intensely anti-communist and defended McCarthy (a fellow Irish Catholic). Paterfamilias

Joseph Kennedy

Joseph Patrick Kennedy (September 6, 1888 – November 18, 1969) was an American businessman, investor, and politician. He is known for his own political prominence as well as that of his children and was the patriarch of the Irish-American Ken ...

(1888–1969), a very active conservative Democrat, was McCarthy's most ardent supporter and got his son

Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925June 6, 1968), also known by his initials RFK and by the nickname Bobby, was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 64th United States Attorney General from January 1961 to September 1964, ...

a job with McCarthy. McCarthy had talked of "twenty years of treason" (i.e. since Roosevelt's election in 1932). When, in 1953, he started talking of "21 years of treason" and launched a major attack on the Army for promoting a communist dentist in the medical corps, his recklessness proved too much for Eisenhower, who encouraged Republicans to censure McCarthy formally in 1954. The Senator's power collapsed overnight. Senator

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

did not vote for censure. Buckley went on to found the ''

National Review

''National Review'' is an American conservative editorial magazine, focusing on news and commentary pieces on political, social, and cultural affairs. The magazine was founded by the author William F. Buckley Jr. in 1955. Its editor-in-chief i ...

'' in 1955 as a weekly magazine that helped

define the conservative position on public issues.

"McCarthyism" was expanded to include attacks on supposed communist influence in Hollywood, which resulted in the

Hollywood blacklist

The Hollywood blacklist was an entertainment industry blacklist, broader than just Hollywood, put in effect in the mid-20th century in the United States during the early years of the Cold War. The blacklist involved the practice of denying emplo ...

, whereby artists who refused to testify about possible communist connections could not get work. Some famous celebrities (such as

Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin Jr. (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is consider ...

) left the U.S.; other worked under pseudonyms (such as

Dalton Trumbo

James Dalton Trumbo (December 9, 1905 – September 10, 1976) was an American screenwriter who scripted many award-winning films, including ''Roman Holiday'' (1953), ''Exodus'', ''Spartacus'' (both 1960), and ''Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo'' (1944) ...

). McCarthyism included investigations into academics and teachers as well. McCarthyism became a widespread social and cultural phenomenon that affected all levels of society and was the source of a great deal of debate and conflict in the United States. Investigating private citizens for alleged communist affiliations in government, private-industry and in the media produced widespread fear and destroyed the lives of many innocent American citizens. Using innuendo and intense interrogation methods, the "

witch-hunt

A witch-hunt, or a witch purge, is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. The Witch trials in the early modern period, classical period of witch-hunts in Early Modern Europe and European Colon ...

" produced

blacklist

Blacklisting is the action of a group or authority compiling a blacklist (or black list) of people, countries or other entities to be avoided or distrusted as being deemed unacceptable to those making the list. If someone is on a blacklist, t ...

s in several industries. In the course of the anti-communist investigations in the early 1950s

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg

Julius Rosenberg (May 12, 1918 – June 19, 1953) and Ethel Rosenberg (; September 28, 1915 – June 19, 1953) were American citizens who were convicted of spying on behalf of the Soviet Union. The couple were convicted of providing top-secret i ...

were charged in relation to the passing of information about the

atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

to the Soviet Union, and they were convicted of conspiracy to commit

espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information (intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tangibl ...

. On June 19, 1953, they were both executed. Their execution was the first of civilians, for espionage, in United States history.

Suez Crisis

The

Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

was a war fought over control of the Suez Canal. It followed the unexpected nationalization of the Suez Canal in 1956 by

Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein, . (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian politician who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 and introduced far-re ...

, in which the United Kingdom, France, and

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

invaded to take control of the canal. The U.S. had strongly warned against military action. The operation was a military success, but the canal was blocked for years to come. Eisenhower demanded the invaders withdraw, and they did. This action was a major humiliation for Britain and France, two Western European countries, and symbolizes the beginning of the end of colonialism and the weakening of European global importance, specifically the collapse of the

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

. The United States then became much more deeply involved in Middle Eastern politics, and remains so into the 21st century.

Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations

In 1953,

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

died, and after the

1952 presidential election, President Dwight D. Eisenhower used the opportunity to end the Korean War, while continuing Cold War policies. Secretary of State

John Foster Dulles

John Foster Dulles (, ; February 25, 1888 – May 24, 1959) was an American diplomat, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. He served as United States Secretary of State under President Dwight D. Eisenhower from 1953 to 1959 and was briefly ...

was the dominant figure in the nation's foreign policy in the 1950s. Dulles denounced the "containment" of the Truman administration and espoused an active program of "liberation", which would lead to a "

rollback

In political science, rollback is the strategy of forcing a change in the major policies of a state, usually by replacing its ruling regime. It contrasts with containment, which means preventing the expansion of that state; and with détente, w ...

" of communism. The most prominent of those doctrines was the policy of "

massive retaliation

Massive retaliation, also known as a massive response or massive deterrence, is a military doctrine and nuclear strategy in which a state commits itself to retaliate in much greater force in the event of an attack.

Strategy

In the event of a ...

", which Dulles announced early in 1954, eschewing the costly, conventional ground forces characteristic of the Truman administration in favor of wielding the vast superiority of the U.S. nuclear arsenal and covert intelligence. Dulles defined this approach as "

brinkmanship

Brinkmanship (or brinksmanship) is the practice of trying to achieve an advantageous outcome by pushing dangerous events to the brink of active conflict. The maneuver of pushing a situation with the opponent to the brink succeeds by forcing the op ...

".

A dramatic shock to Americans' self-confidence and its technological superiority came in 1957, when the Soviets beat the United States into outer space by launching Sputnik, the first earth satellite. The space race began, and by the early 1960s the United States had forged ahead, with President Kennedy promising to land a man on the moon by the end of the 1960s—the landing indeed took place on July 20, 1969.

Trouble close to home appeared when

Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 200 ...

took control of Cuban Revolution, Cuba in 1959 and forged increasingly close ties with the Soviet Union, becoming communism's center in Latin America. The United States responded with an economic boycott of Cuba, and a large-scale economic support program for Latin America under Kennedy, the Alliance for Progress.

East Germany was the weak point in the Soviet Empire, with refugees leaving for the West by the thousands every week. The Soviet solution came in 1961, with the Berlin Wall to stop East Germans from fleeing communism. This was a major propaganda setback for the USSR, but it did allow them to keep control of East Berlin.

The Second World, communist world split in half, as Sino-Soviet split, China turned against the Soviet Union; Mao denounced Khrushchev for going soft on capitalism. However, the US failed to take advantage of this split until President Richard Nixon saw the opportunity in 1969. In 1958, the U.S. sent troops into 1958 Lebanon crisis, Lebanon for nine months to stabilize a country on the verge of civil war. Between 1954 and 1961, Eisenhower dispatched large sums of economic and military aid and 695 military advisers to South Vietnam to stabilize the pro-western government under attack by insurgents. Eisenhower supported CIA efforts to undermine anti-American governments, which proved most successful 1953 Iranian coup d'état, in Iran and 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état, in Guatemala.

The first major strain among the NATO alliance occurred in 1956 when Eisenhower forced Britain and France to retreat from their Suez Crisis, invasion of Egypt (with

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

) which was intended to get back their ownership of the Suez Canal. Instead of supporting the claims of its NATO partners, the Eisenhower administration stated that it opposed French and British imperial adventurism in the region by sheer prudence, fearing that Egyptian leader

Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein, . (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian politician who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 and introduced far-re ...

's standoff with the region's old colonial powers would bolster Soviet power in the region.

The Cold War reached its most dangerous point during the Kennedy administration in the

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

, a tense confrontation between the Soviet Union and the United States over the Soviet deployment of nuclear missiles in Cuba. The crisis began on October 16, 1962, and lasted for thirteen days. It was the moment when the Cold War was closest to exploding into a devastating nuclear exchange between the two superpower nations. Kennedy decided not to invade or bomb Cuba but to institute a naval blockade of the island. The crisis ended in a compromise, with the Soviets removing their missiles publicly, and the United States secretly removing its nuclear missiles in Turkey. In Moscow, communist leaders removed Nikita Khrushchev because of his reckless behavior.

Americas

*In the 1950s, Latin America was the center of covert and overt conflict between the Soviet Union and the United States. Their varying collusion with national, populist, and elitist interests destabilized the region. The United States Central Intelligence Agency orchestrated the overthrow of the Guatemalan government (Operation PBSuccess) in 1952.

*In 1958, the military dictatorship of Venezuela was overthrown. This continued a pattern of regional revolution and warfare making extensive use of ground forces.

*In 1957, Dr. François Duvalier came to power in an election in Haiti. He later declared himself president for life, and ruled until his death in 1971.

*In 1959,

Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 200 ...

overthrew the regime of Fulgencio Batista in Cuba, establishing a communist government in the country. Although Castro initially sought aid from the US, he was rebuffed and later turned to the Soviet Union.

*NORAD signed in 1959 by Canada and the United States creating a unified North American aerial defense system.

Cuban Revolution

The overthrow of Fulgencio Batista by

Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 200 ...

, Che Guevara and other forces in 1959 resulted in the creation of the first communist government in the western hemisphere. The

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis (of 1962) ( es, Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, the Caribbean Crisis () in Russia, or the Missile Scare, was a 35-day (16 October – 20 November 1962) confrontation between the United S ...

of 1962 led to a confrontation between the United States, Cuba, and the Soviet Union.

Indonesia

In Indonesia in February 1958 rebels on Sumatra and Sulawesi declared the Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Indonesia, PRRI-Permesta Movement aimed at overthrowing the government of Sukarno. Due to their anti-communist rhetoric, the rebels received money, weapons, and manpower from the Central Intelligence Agency, CIA. This support ended when Allen Lawrence Pope, an American pilot, was shot down after a bombing raid on government-held Ambon, Maluku, Ambon in April 1958. In April 1958, the central government responded by launching airborne and seaborne military invasions on Padang, Indonesia, Padang and Manado, the rebel capitals. By the end of 1958, the rebels had been militarily defeated, and the last remaining rebel guerrilla bands surrendered in August 1961.

Society

At the center of middle-class culture in the 1950s was a growing demand for consumer goods; a result of the postwar prosperity, the increase in variety and availability of consumer products, and television advertising. America generated a steadily growing demand for better automobiles, clothing, appliances, family vacations and higher education. After the initial hurdles of the 1945-48 period were overcome, Americans found themselves flush with cash from wartime work due to there being little to buy for several years. The result was a mass consumer spending spree, with a huge and voracious demand for new homes, cars, and housewares. Increasing numbers enjoyed high wages, larger houses, better schools, more cars and home comforts like vacuum cleaners, washing machines—which were all made for labor-saving and to make housework easier. Inventions familiar in the early 21st century made their first appearance during this era. The live-in maid and cook, common features of middle-class homes at the beginning of the century, were virtually unheard of in the 1950s; only the very rich had servants. Householders enjoyed centrally heated homes with running hot water. New style furniture was bright, cheap, and light, and easy to move around. As noted by John Kenneth Galbraith in 1958:

:"the ordinary individual has access to amenities – foods, entertainments, personal transportation, and plumbing – in which not even the rich rejoiced a century ago."

Economy

Wartime rationing was officially lifted in September 1945, but prosperity did not immediately return as the next three years would witness the difficult transition back to a peacetime economy. Twelve million returning veterans were in need of work and in many cases could not find it. Inflation became a rather serious problem, averaging over 10% per year until 1950 and raw materials shortages dogged the manufacturing industry. In addition, labor strikes rocked the nation and were in some cases exacerbated by racial tensions: African-Americans that took jobs during the war were faced with irate returning veterans who demanded that they step aside. Munitions factories shut down and temporary workers returned home. Following the Republican takeover of Congress in the 1946 elections, President Truman was compelled to reduce taxes and curb government interference in the economy. With this done, the stage was set for the economic boom that, with only a few minor hiccups, would last for the next 23 years. Between 1945 and 1960, GNP grew by 250%, expenditures on new construction multiplied nine times, and consumption on personal services increased three times. By 1960, per capita income was 35% higher than in 1945, and America had entered what the economist Walt Rostow referred to as the "high mass consumption" stage of economic development. Short-term credit went up from $8.4 billion in 1946 to $45.6 billion in 1958. As a result of the postwar economic boom, 60% of the American population had attained a "middle-class" standard of living by the mid-1950s (defined as incomes of $3,000 to $10,000 in constant dollars), compared with only 31% in the last year of prosperity before the onset of the Great Depression in 1929. By the end of the decade, 87% of families owned a TV set, 75% owned a car, and 75% owned a washing machine. Between 1947 and 1960, the average real income for American workers increased by as much as it had in the previous half-century.

[The Unfinished Journey: America Since World War II by William H. Chafe]

Prosperity and overall optimism made Americans feel that it was a good time to bring children into the world, and so a huge baby boom resulted during the decade following 1945 (the baby boom climaxed during the mid-1950s, after which time birthrates gradually declined until going below replacement level in 1965). Although the overall number of children per woman was not unusually high (averaging 2.3), they were assisted by improving technology that greatly brought down infant mortality rates versus the prewar era. Among other things, this resulted in an unprecedented demand for children's products and a huge expansion of the public school system. The large size of the postwar baby-boom generation would have significant social repercussions in American society for decades to come.

In addition to the huge domestic market for consumer items, the United States became "the world's factory", as it was the only major power whose soil had been untouched by the war. American money and manufactured goods flooded into Europe, South Korea, and Japan and helped in their reconstruction. US manufacturing dominance would be almost unchallenged for a quarter-century after 1945.

The American economy grew dramatically in the post-war period, expanding at a rate of 3.5% per year between 1945 and 1970. During this period of prosperity, many incomes doubled in a generation, described by economist Frank Levy as "upward mobility on a rocket ship." The substantial increase in average family income within a generation resulted in millions of office and factory workers being lifted into a growing middle class, enabling them to sustain a standard of living once considered to be reserved for the wealthy. As noted by Deone Zell, assembly-line work paid well, while unionized factory jobs served as "stepping-stones to the middle class."

[Changing by design: organizational innovation at Hewlett-Packard by Deone Zell] By the end of the 1950s, 87% of all American families owned at least one T.V., 75% owned cars, and 60% owned their homes.

[Nation's business: Volume 48, Chamber of Commerce of the United States of America, 1960] By 1960, blue-collar workers had become the biggest buyers of many luxury goods and services.

In addition, by the early-1970s, post-World War II American consumers enjoyed higher levels of disposable income than those in any other country.

The great majority of American workers who had stable jobs were well-off financially, while even non-union jobs were associated with rising paychecks, benefits, and obtained many of the advantages that characterized union work. An upscale working class came into being, as American blue-collar workers came to enjoy the benefits of home ownership, while high wages provided blue-collar workers with the ability to pay for new cars, household appliances, and regular vacations.

[Promises Kept: John F. Kennedy's New Frontier by Irving Bernstein] By the 1960s, a blue-collar worker earned more than a manager did in the 1940s, despite the fact that the former's relative position within the income distribution had not changed.

As noted by the historian Nancy Wierek:

:"In the postwar period, the majority of Americans were affluent in the sense that they were in a position to spend money on many things they wanted, desired, or chose to have, rather than on necessities alone."

As argued by the historians Ronald Edsforth and Larry Bennett:

:"By the mid-1960s, the majority of America's organized working class who were not victims of the second Red Scare embraced, or at least tolerated, anti-communism because it was an integral part of the New American Dream to which they had committed their lives. Theirs was not an unobtainable dream; nor were their lives empty because of it. Indeed, for at least a quarter of century, the material promises of consumer-oriented Americanism were fulfilled in improvements in everyday life that made them the most affluent working class in American history."

Between 1946 and 1960, the United States witnessed a significant expansion in the consumption of goods and services. GNP rose by 36% and personal consumption expenditures by 42%, cumulative gains which were reflected in the incomes of families and unrelated individuals. While the number of these units rose sharply from 43.3 million to 56.1 million in 1960, a rise of almost 23%, their average incomes grew even faster, from $3,940 in 1946 to $6,900 in 1960, an increase of 43%. After taking inflation into account, the real increase was 16%. The dramatic rise in the average American standard of living was such that, according to sociologist George Katona:

:"Today in this country minimum standards of nutrition, housing and clothing are assured, not for all, but for the majority. Beyond these minimum needs, such former luxuries as homeownership, durable goods, travel, recreation, and entertainment are no longer restricted to a few. The broad masses participate in enjoying all these things and generate most of the demand for them."

More than 21 million housing units were constructed between 1946 and 1960, and in the latter year 52% of consumer units in the metropolitan areas owned their own homes. In 1957, out of all the wired homes throughout the country, 96% had a refrigerator, 87% an electric washer, 81% a television, 67% a vacuum cleaner, 18% a freezer, 12% an electric or gas dryer, and 8% air conditioning. Car ownership also soared, with 72% of consumer units owning an automobile by 1960.

From 1958 to 1964, the average weekly take-home pay of blue-collar workers rose steadily from $68 to $78 (in constant dollars). In a poll taken in 1949, 50% of all Americans said that they were satisfied with their family income, a figure that rose to 67% by 1969.

The period from 1946 to 1960 also witnessed a significant increase in the paid leisure time of working people. The forty-hour workweek established by the Fair Labor Standards Act in covered industries became the actual schedule in most workplaces by 1960, while uncovered workers such as farmworkers and the self-employed worked fewer hours than they had done previously, although they still worked much longer hours than most other workers. Paid vacations also came to be enjoyed by the vast majority of workers, with 91% of blue-collar workers covered by major collective bargaining agreements receiving paid vacations by 1957 (usually to a maximum of three weeks), while by the early-1960s virtually all industries paid for holidays and most did so for seven days a year. Industries catering to leisure activities blossomed as a result of most Americans enjoying significant paid leisure time by 1960,

while many blue-collar and white-collar workers had come to expect to hold on to their jobs for life. This period saw the growth of motels along major highways, as well as amusement parks such as Disneyland, which opened in 1955.

Educational outlays were also greater than in other countries while a higher proportion of young people were graduating from high schools and universities than elsewhere in the world, as hundreds of new colleges and universities opened every year. Tuition was kept low—it was free at California state universities. At the advanced level, American science, engineering, and medicine was world-famous. By the mid-1960s, the majority of American workers enjoyed the highest wage levels in the world, and by the late-1960s, the great majority of Americans were richer than people in other countries, except Sweden, Switzerland, and Canada. Educational outlays were also greater than in other countries while a higher proportion of young people was at school and college than elsewhere in the world. As noted by the historian John Vaizey:

:"To strike a balance with the Soviet Union, it would be easy to say that all but the very poorest Americans were better off than the Russians, that education was better but the health service worse, but that above all the Americans had freedom of expression and democratic institutions."

In regards to social welfare, the post-war era saw a considerable improvement in insurance for workers and their dependents against the risks of illness, as private insurance programs like Blue Cross and Blue Shield expanded. With the exception of farm and domestic workers, virtually all members of the labor force were covered by Social Security. In 1959, about two-thirds of the factory workers and three-fourths of the office workers were provided with supplemental private pension plans. In addition, 86% of factory workers and 83% of office workers had jobs that covered for hospital insurance while 59% and 61% had additional insurance for doctors.

By 1969, the average White Americans, White family income had risen to $10,953, while the average Black Americans, Black family income lagged behind at $7,255, revealing a continued racial disparity in income among various segments of the American population. The percentage of American students continuing their education after the age of fifteen was also higher than in most other developed countries, with more than 90% of 16-year-olds and around 75% of 17-year-olds in school in 1964–66.

Despite overall prosperity during the 1950s, economic growth only averaged 2% a year during Eisenhower's administration, and Federal income taxes remained extremely high at over 90%, although tax evasion was common with the porous tax code of the time. There were also three recessions: the first in 1953-54 following the end of the Korean War, the second in 1958, and the third in 1960–61. In each case, the Republican Party, which had begun the Eisenhower era with a plurality in Congress, suffered the consequences. In the 1954 midterms, the Democrats regained a solid majority of both houses and they would retain unbroken control of the Senate until 1981 and the House until 1995. The 1958 recession cost the GOP yet more seats, and the 1960 recession was used by John F. Kennedy as cannon fodder against the Republicans in his presidential run.

Unemployment peaked at 7% in the spring of 1961 before an economic rebound began that would continue to the end of the decade. President Kennedy then decided to break with the New Deal orthodoxy of high Federal taxes to force income equality. In a December 1962 speech, he announced his plans to reduce the top marginal tax rate to 75%, which one GOP Congressman wryly dubbed "the most Republican speech a president has made since McKinley". Although the president did not live to see his tax proposal passed, Lyndon Johnson quickly steered it through Congress, and by late-1965, real GDP growth was exceeding 6% a year.

Cars

Automobiles became much more available, after the low production runs in the Depression, followed by the moratorium on production during the Second World War, when factories produced Jeeps and other military transport vehicles instead of cars. Styles became flashier. Boxy and conservative in the first half of the decade, they became lower, longer, wider, and sleeker. Tail fins, chrome, and multicolor paint jobs characterized the late 1950s. It was the beginning of the end for the small auto manufacturers, which were crippled by the Ford-GM price war of 1953–1954. Studebaker went under; the others merged into American Motors, whose Nash Rambler, Rambler chugged into the 1960s.

Ford's launch of the new Edsel in 1958 was hotly anticipated, but it was a lemon and was cancelled after only three years. The name "Edsel" became an icon of failure. The 1950s was also the decade when the popular sport Formula One started.

Suburbia

Very little housing had been built during the Great Depression and World War, except for emergency quarters near war industries. Overcrowded and inadequate apartments was the common condition. Some suburbs had developed around large cities where there was rail transportation to the jobs downtown. However, the real growth in suburbia depended on the availability of automobiles, highways, and inexpensive housing. The population had grown, and the stock of family savings had accumulated the money for down payments, automobiles and appliances. The product was a great housing boom. Whereas an average of 316,000 new housing nonfarm units had been constructed each year from the 1930s through 1945, there were 1,450,000 built annually from 1946 through 1955 in all areas, especially suburbs. The G.I. Bill guaranteed low cost loans for veterans, with very low down payments, and low interest rates. With 16,000,000 eligible veterans, the opportunity to buy a house was suddenly at hand. In 1947 alone, 540,000 veterans bought one; their average price was $7,300 (equal to $84,000 in 2020). The construction industry kept prices low by standardization – for example standardizing sizes for kitchen cabinets, refrigerators, and stoves allowed for mass production of kitchen furnishings. Developers purchased empty land just outside the city, installed tract houses based on a handful of designs, and provided streets and utilities, as local public officials race to build schools. The most famous development was Levittown, New York, Levittown, in Long Island just east of New York City. It offered a new house for $1,000 down, and $70 a month; it featured three bedrooms, fireplace, gas range and gas furnace, and a landscaped lot of 75 by 100 feet, all for a total price of $10,000. Veterans could get one with a much lower down payment. Growth of the suburbs was especially prominent in the Sunbelt regions of the country; one example of a suburb on the West Coast was Lakewood, California, built largely to serve family of aviation workers. Going hand-in-hand with suburban development was the rise of shopping malls, fast-food restaurants and Diner, coffee shops.

With Detroit turning out automobiles as fast as possible, city dwellers gave up cramped apartments for a suburban life style centered around children and housewives, with the male breadwinner commuting to work. Suburbia encompassed one-third of the nation's population by 1960. The growth of suburbs was not only a result of postwar prosperity, but innovations of the single-family housing market with low interest rates on 20 and 30 year mortgages, and low down payments, especially for veterans. Meanwhile, the suburban population swelled because of the post–World War II baby boom, baby boom. Suburbs provided larger homes for larger families, security from urban living, privacy, and space for consumer goods.

Science, technology, and futurism

With the prosperity of the era, the prevailing social attitude was one of belief in science, technology, progress, and futurism, although there had been signs of this trend since the 1930s. There was comparatively little nostalgia for the prewar era and the overall emphasis was on having everything new and more advanced than before. Nonetheless, the social conformity and consumerism of the 1950s often came under attack from intellectuals (e.g. Henry Miller's books ''The Air-Conditioned Nightmare'' and ''Sunday After The War'') and there was a good deal of unrest fermenting under the surface of American society that would erupt during the following decade.

One of the key factors in postwar prosperity was a technology boom due to the experience of the war. Manufacturing had made enormous strides and it was now possible to produce consumer goods in quantities and levels of sophistication unseen before 1945. Acquisition of technology from occupied Germany also proved an asset, as it was sometimes more advanced than its American counterpart, especially in the optics and audio equipment fields. The typical automobile in 1950 was an average of $300 more expensive than the 1940 version, but also produced in twice the numbers. Luxury brands such as Cadillac, which had been largely hand-built vehicles only available to the rich, now became a mass-produced car within the price range of the upper middle-class.

The rapid social and technological changes brought about a growing corporatization of America and the decline of smaller businesses, which often suffered from high postwar inflation and mounting operating costs. Newspapers declined in numbers and consolidated, both due to the above-mentioned factors and the event of TV news. The railroad industry, once one of the cornerstones of the American economy and an immense and often scorned influence on national politics, also suffered from the explosion in automobile sales and the construction of the interstate system. By the end of the 1950s, it was well into decline and by the 1970s became completely bankrupt, necessitating a takeover by the federal government. Smaller automobile manufacturers such as Nash Motors, Nash, Studebaker, and Packard were unable to compete with the Big Three in the new postwar world and gradually declined into oblivion over the next fifteen years. Suburbanization caused the gradual movement of working-class people and jobs out of the inner cities as shopping centers displaced the traditional downtown stores. In time, this would have disastrous effects on urban areas.

Major technological events of this period include:

* The Miller–Urey experiment showed in 1953 that under simulated conditions resembling those thought to be possible to have existed shortly after Earth was first created, many of the basic organic molecules that form the building blocks of life are able to spontaneously form.

* Francis Crick, and James D. Watson, discovered the helical structure of DNA at the Cavendish Laboratory at the University of Cambridge in 1953.

* Bruce C. Heezen discovered the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

* The first polio vaccine, developed by Jonas Salk, Dr. Jonas Salk, was introduced to the general public in 1955.

* The first Organ transplant, organ transplants were done in Boston and Paris in 1954.

* The term artificial intelligence was coined in 1956 by John McCarthy (computer scientist), John McCarthy.

* Sputnik 1 was launched in 1957. The US then launched Explorer 1 three months later, beginning the space race.

* Fortran, perhaps the single most important milestone in the development of programming languages, was developed at IBM.

* The Kinsey Reports were published.

* NASA is organized.

Poverty and inequality in the postwar era

Despite the prosperity of the postwar era, a significant minority of Americans continued to live in poverty by the end of the 1950s. In 1947, 34% of all families earned less than $3,000 a year, compared with 22.1% in 1960. Nevertheless, between one-fifth to one-quarter of the population could not survive on the income they earned. The older generation of Americans did not benefit as much from the postwar economic boom especially as many had never recovered financially from the loss of their savings during the Great Depression. It was generally a given that the average 35-year-old in 1959 owned a better house and car than the average 65-year-old, who typically had nothing but a small Social Security pension for an income. Many blue-collar workers continued to live in poverty, with 30% of those employed in industry in 1958 receiving under $3,000 a year. In addition, individuals who earned more than $10,000 a year paid a lower proportion of their income in taxes than those who earned less than $2,000 a year.

In 1947, 60% of black families lived below the poverty level (defined in one study as below $3000 in 1968 dollars), compared with 23% of white families. In 1968, 23% of black families lived below the poverty level, compared with 9% of white families. In 1947, 11% of white families were affluent (defined as above $10,000 in 1968 dollars), compared with 3% of black families. In 1968, 42% of white families were defined as affluent, compared with 21% of black families. In 1947, 8% of black families received $7000 or more (in 1968 dollars) compared with 26% of white families. In 1968, 39% of black families received $7,000 or more, compared with 66% of white families. In 1960, the median for a married man of blue-collar income was $3,993 for blacks and $5,877 for whites. In 1969, the equivalent figures were $5,746 and $7,452, respectively.

As Socialist leader Michael Harrington emphasized, there was still The Other America. Poverty declined sharply in the 1960s as the New Frontier and

Great Society

The Great Society was a set of domestic programs in the United States launched by Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964–65. The term was first coined during a 1964 commencement address by President Lyndon B. Johnson at the University ...

especially helped older people. The proportion below the poverty line fell almost in half from 22% in 1960 to 12% in 1970 and then leveled off.

Rural life

The farm population shrank steadily as families moved to urban areas, where on average they were more productive and earned a higher standard of living. Friedberger argues that the postwar period saw an accelerating mechanization of agriculture, combined with new and better fertilizers and genetic manipulation of hybrid corn. It made for greater specialization and greater economic risks for the farmer. With rising land prices many sold their land and moved to town, the old farm becoming part of a neighbor's enlarged operation. Mechanization meant less need for hired labor; farmers could operate more acres even though they were older. The result was a decline in rural-farm population, with gains in service centers that provided the new technology. The rural non-farm population grew as factories were attracted by access to good transportation without the high land costs, taxes, unionization and congestion of city factory districts. Once remote rural areas such as the Missouri Ozarks and the North Woods of the upper Midwest, with a rustic life style and many good fishing spots, attracted retirees and vacationers.

Culture

Key events

* The popularity of television skyrocketed, particularly in the US, where 77% of households purchased their first TV set during the decade.

*The social mores about Human sexual activity, sex were particularly restrictive, characterized by strong taboos and a nervous attitude for prudish conformity, to the point that even the softcore pornography of the time avoided describing it.

[Thomas Pynchon (1984) ''Slow Learner'', pp.6-7] The social mores of the decade were marked by overall conservatism and conformity.

* ''The Day the Earth Stood Still'' hits movie theaters launching a cycle of Hollywood films in which Cold War fears are manifested through scenarios of alien invasion or mutation.

* Resurgence of evangelical Christianity including Youth for Christ (1943); the National Association of Evangelicals, the American Council of Christian Churches, the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (1950), Conservative Baptist Association of America (1947); and Campus Crusade for Christ (1951). ''Christianity Today'' was first published in 1956. 1956 also marked the beginning of Bethany Fellowship, a small press that grew to be a leading evangelical press.

* Carl Stuart Hamblen, a religious radio broadcaster, hosted the popular show "The Cowboy Church of the Air".

*Hugh Hefner launched ''Playboy'' magazine in 1953.

* ''Disneyland'' opens in July 1955.

Fine Arts

Abstract expressionism, the first specifically American art movement to gain worldwide influence, was responsible for putting New York City in the centre on the artistic world, a place previously owned by Paris, France. This movement acquired its name for combining the German expressionism's emotional intensity with the anti-figurative aesthetic of the European abstract schools such as Futurism, Bauhaus and Synthetic Cubism. Jackson Pollock was one of the most influential painters of this movement, creating famous works such as No. 5, 1948.

Color Field painting and Hard-edge painting followed close on the heels of Abstract expressionism, and became the idiom for new abstraction in painting during the late 1950s. The term ''second generation'' was applied to many abstract artists who were related to but following different directions than the early abstract expressionists.

Bay Area Figurative Movement was an important return to figuration and a reaction against abstract expressionism by artists living and working on the West Coast of the United States, West Coast in and around San Francisco during the mid-1950s.

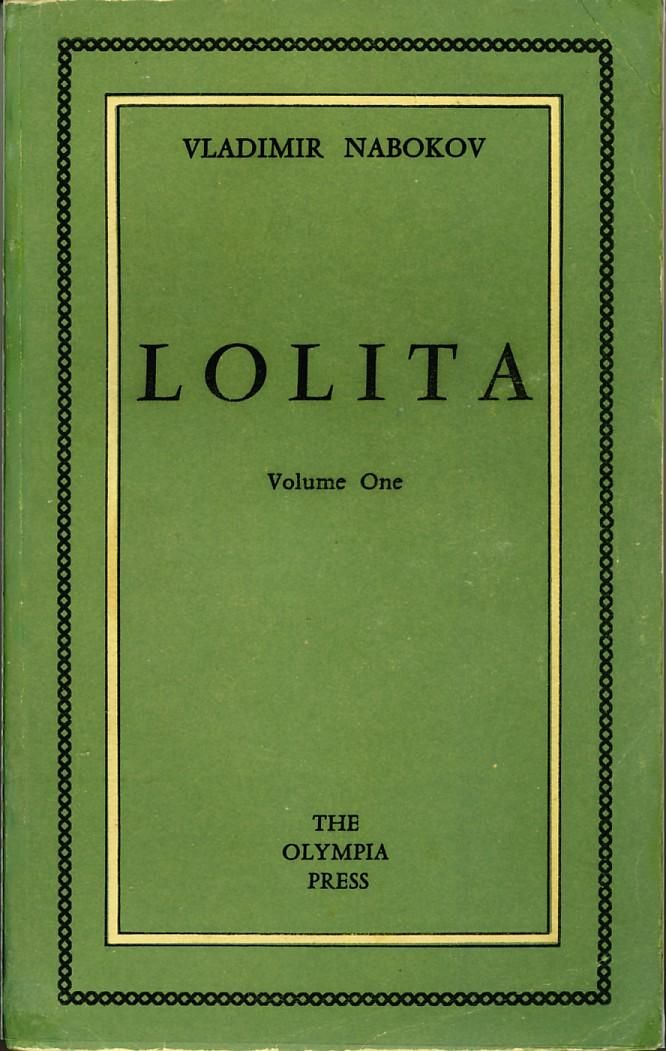

Literature

The strong sexual taboos of mass culture were also reflected in literature, with the institutionally established modernist tradition, and most writers feeling compelled to self-censor themselves.

This would clash with the Beat fiction which pushed the boundaries of what was considered allowed, causing a liberating and exciting cultural effect which encouraged other writers to free up. For this, the Beat movement was met with a series of censorships and law enforcement excesses.

One of the most influential and most highly critically acclaimed of the many books about the era is ''The Fifties (book), The Fifties'' by journalist and author David Halberstam.

Beatniks and the Beat Generation, an anti-materialistic literary movement whose name was invented by Jack Kerouac in 1948 and stretched on into the early-mid-1960s, was at its zenith in the 1950s. Such groundbreaking literature from the beats includes William S. Burroughs' ''Naked Lunch'', Allen Ginsberg's ''Howl (poem), Howl'', and Jack Kerouac's ''On the Road''. This decade is also marked by some of the most famous works of science fiction by science fiction writers Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, Ray Bradbury, Theodore Sturgeon, A. E. van Vogt, and Robert A. Heinlein.

Though it was not published until 1960, John Updike's ''Rabbit, Run'' was written during and exemplifies the culture of the 1950s. The novel ''Revolutionary Road'' by Richard Yates (novelist), Richard Yates, published in 1961, is concerned with mid-1950s life and culture. Sylvia Plath's "The Bell Jar", though not published until 1963, features a woman's struggle living in 1950s American culture. Agatha Christie was also at a stage where she published at an average rate of one book every year.

In 1963, Betty Friedan published her book ''The Feminine Mystique'' which ridiculed the housewife role of women during the postwar years; it was a best-seller and a major catalyst of the women's liberation movement.

Fashion

The 1950s were a time of fashion evolution. At the beginning of the decade, fitted blouses and jackets with rounded (as opposed to puffy) shoulders and small, round collars were very popular.

Narrow pant legs and capris became increasingly popular during this time, often worn with flats, ballet-inspired shoes, and Keds/Converse (shoe company), Converse type sneakers (footwear), sneakers. Thick, heavy heels were popular for low shoes. Socks were sometimes worn, but were not as necessary as they are now. Circle skirts (like the classic poodle skirt) were very popular. They were often hand decorated with various patterns or beads to make them unique

and worn over petticoats. Shirt dresses with large, contrasting buttons were also stylish. Early 1950s women wore small hats over hair cut short, à la Audrey Hepburn.

As the 1950s progressed, so too did fashion, until, by the end of the 1950s, the Jackie Kennedy look was in style. A-line (clothing), A-lines and loose-fitting dresses became more and more popular, and jackets took on a boxy look.

Kitten heels and metal/Stiletto heel, steel stilettos became the most popular shoe style. Flower-pot shaped hats overtook the small ones of earlier in the decade, and large hairstyles, such as that of Liz Taylor, were in.

Prosperity also brought about the development of a distinct youth culture for the first time, as teenagers were not forced to work and support their family at young ages like in the past. This had its culmination in the development of new music genres such as rock-and-roll as well as fashion styles and subcultures, the most famous of which was the "greaser", a young male who drove motorcycles, sported ducktail haircuts (which were widely banned in schools) and displayed a general disregard for the law and authority. The greaser phenomenon was kicked off by the controversial youth-oriented movies ''The Wild One'' (1953) starring Marlon Brando and ''Rebel Without A Cause'' (1955) starring James Dean.

Music